Hidden within the boundaries of the Tonto National Forest, only a few minutes' drive north of Phoenix, stands a network of ancient Hohokam hill-forts, holding silent vigil over what was once a substantial agrarian community. That these are defensive fortifications is obvious even to the casual observer: many are built far from water, perched in inaccessible and easily defended locations with excellent visibility of the surrounding terrain. But the telling feature that distinguishes all such sites is an outer perimeter wall, some of which still stand up to eight feet in height.

Large ruins are common in this area, but most are constructed in "massed room block" style--multiple contiguous rooms that share common walls, with each room small enough to be spanned by roof timbers. Most of the large ruins in the Agua Fria National Monument are of this type construction. The walls around the Tonto hill-forts, however, are not shared by any of the enclosed buildings, and are much too large to have ever supported a roof. In a society that did not have domesticated livestock, in a region without dangerous animals, that leaves only one explanation for such a labor-intensive feature: defense against human attack.

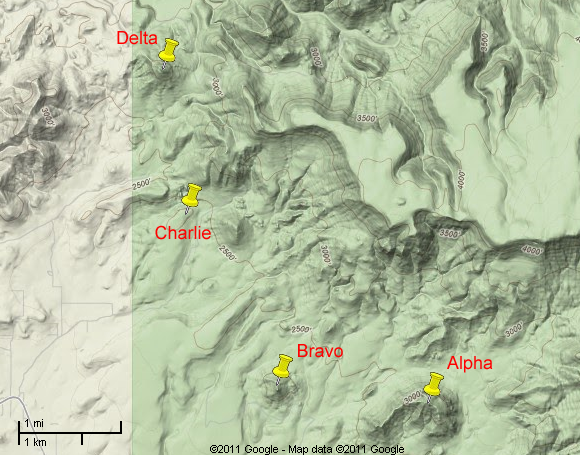

This page describes a chain of four such forts, each one line-of-sight visible to the next. For convenience, we have named them "Alpha," "Bravo," "Charlie," and "Delta." There are almost certainly more in the chain that remain undiscovered. Any information from readers would be appreciated.

Due to their proximity to populated areas, we are being very circumspect about the locations of these fragile sites. We ask anyone who knows of them to be equally cautious, and to treat them with respect.

Relative Locations of Tonto Hill-Forts

The Alpha Site fort sits on the highest point of a horseshoe-shaped serrated ridgeline. There is no trail to the top, and the way is steep. But the view is excellent, providing a sweeping panorama of the surrounding terrain and distant mesas.

The route we chose passed over the tops of some low foothills, where we chanced upon a cluster of petroglyphs, one of which appears to show a man on a horse (photo A-7). If this is indeed what it is, it is an interesting find. The fortress was contemporaneous with the Hohokam, and was abandoned no later than the thirteenth century. Horses, of course, were introduced to the Americas by the Spanish, and would not have been seen in this area until the sixteenth century or later. It is possible, however, that there is a more prosaic explanation for the horse-and-rider image. Petroglyphs are difficult to date, and this one may have been created in modern times. Or it could simply depict a man standing behind a deer or elk. Readers will have to decide for themselves.

There is another minor mystery associated with the Apha-site ruin. Along the perimeter wall, only a foot or two above the ground, one will occasionally notice a carefully-constructed hole that passes through the wall at a slight downward angle (photos A-8 and A-9). The purpose of these holes is not clear. The view through them is too restrictive for use as spy-holes. Whatever their purpose, this feature is not unique to the Alpha-site: photo A-10 shows one of several similar holes in the walls of Black Canyon Fort, thirty miles away.

Of the four sites visited, Bravo is in the worst condition. Its walls, invisible from any distance, are almost entirely gone, their remnants strewn across the flanks of the hill. Enough remains, however, to provide a picture of what once was an extensive series of rooms and walls surrounding the peak like a medieval castle. There are also the remains of larger structures on the shoulder below the peak. These lack a perimeter wall, however, and were probably not defensive in nature.

Photo B-10 shows a collection of pot sherds, placed there by previous visitors. In case you're wondering, here is the rule: Do not collect pot sherds like this. Removing them from their original context destroys much of their archeological value. However, if you find such a collection, do not take it upon yourself to redistribute the shards. The damage is done, and sprinkling them randomly will do more harm than good.

Charlie site is the largest fort in the chain. It is also the least well protected in terms of natural barriers, being located on a low, gently sloping hill. There are several other ruin clusters further along the ridge, but Charlie is the only one with a defensive wall. It is likely this site provided protection and a point of retreat for a fairly large community.

The perimeter wall here is thick, and much of it still stands. There are also the remains of some internal buildings, though these are in worse condition. The ground is littered with pot sherds large and small.

Delta Site is the northern-most fort in the chain, and the hardest to reach. Just to get within hiking distance requires a solid 4WD vehicle, which will depart with less paint than it arrived with. The ascent itself is short but challenging, with the last thirty feet requiring a nearly vertical climb up the caprock (photo D-4). There are only a few ways up, and these have been lined at the top with stone walls, carefully designed to channel visitors into narrow slots (photos D-8 and D-9). One or two people at each of these entrances could probably hold off an army, at least until they ran out of rocks to throw. Unsurprisingly, the view from the top is spectacular. One wonders if the people who built these places appreciated the beauty of their surroundings.