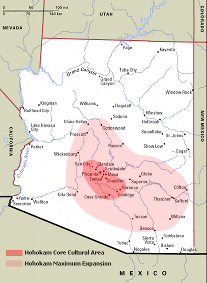

The Hohokam were a prehistoric people that inhabited the Sonoran desert of central Arizona from about AD 300 to AD 1400. Occupying the region around modern-day Phoenix along the Salt and Gila Rivers, the Hohokam were one of several relatively advanced cultures in the American Southwest during that period. The others include the Anasazi, centered around the Four Corners region where Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah meet; the Sinagua, located around Flagstaff and along the Verde River of Arizona; and the Mogollon, who occupied eastern Arizona, southern New Mexico, and portions of the northern Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua. For reasons that are still not completely understood, all of these cultures went into a sudden and permanent decline between approximately 1350 and 1450 AD, about a hundred years before contact with Europeans.

The name "Hohokam" is from the language of the Akimel and Tohono O'odham people, two present-day Native American communities in central Arizona that claim the Hohokam as their ancestors. The word means, poignantly enough, "all used up."

Archaeologists have identified multiple chronological phases of Hohokam culture, based on changes in geographic extent, pottery styles, architecture, canal building, and other attributes. These phases, known as the Hohokam Sequence, are shown below. Note that these dates are approximate, and vary slightly from source to source. Some researchers mark the beginning of Hohokam culture as early 1 AD, and its demise as late as 1450.

| The Hohokam Sequence | |

|---|---|

| Dates | Name |

| AD 300 - 775 | Pioneer Period |

| AD 775 - 975 | Colonial Period |

| AD 975 - 1150 | Sedentary Period |

| AD 1150 - 1400 | Classic Period |

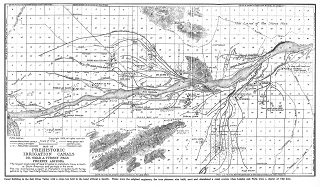

One of the characteristics for which the Hohokam are justly famous is their extensive canal system. Sometime around AD 600 the Hohokam began constructing canals to provide reliable irrigation to crops of corn, beans and squash—the staples of Hohokam diet. Over the next several hundred years, these canals were widened and extended to support larger agricultural areas further away from the perennial rivers sources.

The system was carefully engineered, with large main canals diverting water from the Salt and Gila Rivers, and branching out in a series of smaller secondary and tertiary canals designed to maintain constant flow rates and to minimize erosion and maintain sediment transport. The canals followed the contours of the land, achieving a gradient of only one to two feet per mile—a remarkable degree of precision even by modern standards.

The ground in the Phoenix Basin consists primarily of caliche, a sedimentary rock amalgam held together with a hardened natural cement of calcium carbonate. It is extremely hard and difficult to excavate, even using modern equipment. The amount of effort required to dig canals, some of which were over twelve feet deep, using stone tools and human muscle power is truly impressive, and indicates a high degree of social organization.

By 1300 the Hohokam had created the largest canal system in prehistoric North America, with 500 miles of canals providing irrigation to over 100,000 acres of cropland. The system provided food for an estimated 80,000 people with the highest population density in the ancient Southwest.

By the time Europeans arrived in the Phoenix Basin, the canal system had long been abandoned. Much of it was still visible, however, and early settlers took advantage by cleaning out the old waterways and weirs and using them to irrigate their own crops. The remains of these ancient canals are still present throughout modern Phoenix and the surrounding areas, and are an active subject of archaeological research.

Another hallmark of Hohokam culture is the ballcourt. A ballcourt is an oval, bowl-shaped depression in the ground typically 100 feet long by 50 feet wide (although there is wide variation). They are constructed by excavating the interior of the oval and piling the dirt up in a berm around the perimeter, providing a sloping wall up to nine feet in height. The assumption is that contestants played some form of ballgame inside the oval, with spectators watching from atop the surrounding berm.

Over 200 ballcourts have been identified in the Hohokam region, with more than 30 found in the Salt River Valley alone. They were constructed and used over a 500 year period from about AD 750 to 1200, roughly corresponding to the Colonial and Sedentary periods. There are ballcourts at virtually all Hohokam settlements, including one each at Casa Grande Ruin and Snaketown, and as many as three at the Pueblo Grande platform mound in downtown Phoenix.

Although the presence of ballcourts had been noted in the archaeological literature as far back as the nineteenth century, initially no one knew what they were for. Early theories were that they were water reservoirs, areas for threshing crops, or even "sun temples." Then the famous archaeologist Emil W. Haury uncovered a ballcourt during his 1934-1935 excavation of Snaketown, a Hohokam settlement on the Gila River between Phoenix and Tucson. Haury noted the structure's similarities to ballcourts found throughout Mesoamerica, and proposed that the Hohokam ballcourts served a similar role. This similarity is one of several lines of evidence used to support the hypothesis of a cultural and trade connection between Mesoamerica and the Southwestern United States.

An unexcavated ballcourt at Casa Grande Ruin.

The Casa Grande Great House is in background.

(Click for larger image)

However, the designation of these structures as "ballcourts" is not without controversy. Mesoamerican ballcourts are rectangular, have flat floors, nearly vertical walls, and are made from stone, whereas the Hohokam version is oval, has floors that slope gradually toward the center, walls that slope at 45 to 60 degrees, and are constructed from excavated earth. Mesoamerican ballcourts have a typical length-to-width ratio of 4-to-1, whereas Hohokam courts are more usually 2-to-1. Also, only two balls (one made of stone, and the other of rubber) have ever been excavated from a Hohokam ballcourt. These differences have led some researchers to propose alternative theories. Donald Brand, a cultural geographer who taught at the University of New Mexico, proposed in 1939 that the "ballcourts" were actually dance plazas. This counterview was later supported by Edwin Ferdon, Assistant Director of the Arizona State University under Emil Haury and a former student of Brand's (yes, archaeology is a small world). In 1967, Ferdon published a paper pointing out the differences between Mesoamerican and Hohokam ballcourts, and proposed that the Hohokam courts are more similar to dance courts used by the Papago. However, subsequent research by David R. Wilcox, Senior Research Anthropologist at the Museum of Northern Arizona and others, has made a compelling case for Haury's original ballcourt interpretation, which remains the prevailing opinion of the archaeological community.

As an interesting aside, ballcourts are not the only communal sports facilities constructed in the pre-Columbian Southwest. North of Phoenix on Perry Mesa and Black Mesa, and near large pueblos such as Polles Mesa along the Verde River, one can find mysterious linear features that archaeologists believe were used as racetracks for ritual footraces. A typical track is 250 meters long, about ten metes wide, and is perfectly straight and cleared of rocks. Dozens of these tracks have been identified, usually associated with large settlements or pueblos. As with the Hohokam ballcourts, the true purpose of the racetracks is a matter of speculation.

Another distinguishing characteristic of Hohokam culture is the platform mound. A typical mound is rectangular in shape, three to ten feet high, and can range from several hundred to several thousand square feet in area.

Over 50 platform mounds have been identified at more than 30 villages throughout the Hohokam cultural area, and there may have been as many as 100 at the peak of the Classic period. All of the mounds were constructed and used fairly late in the Hohokam sequence, between about 1150 and 1300 AD, although some round precursor mounds have been found that date to as early 800 AD. Early mounds do not appear to have had structures on them. However, around 1250 AD, structures and protective walls began to appear on top of the mounds.

A Hohokam Platform Mound at Pueblo Grande Ruin

in Downtown Phoenix

Classic platform mounds were constructed and expanded in stages, by building adobe- and rock-walled "cells" adjacent to the outside of an existing mound and filling it with earth and trash. The flat top of the mound was capped with a layer of calcium carbonate-rich caliche that hardened to form a flat, durable plaster surface. There is some evidence that the mounds and the buildings on top of them may have been painted in bright colors and designs.

Because only a very small percentage of the Hohokam population could have lived on these mounds, the mainstream opinion among archaeologists is that these were residential structures reserved for high-status political or religious leaders and their families. For example, Glen Rice and Charles Redman writing in "Expeditions" magazine in 1993 concluded that

There are platform mounds at most major Hohokam sites, including Pueblo Grande, Mesa Grande, Plaza Tempe and Tres Pueblos. The mounds are always associated with larger communities which include residences, public plazas and storerooms, with the entire compound being surrounded by high walls. These mound compounds are frequently located along major canals at about three mile intervals, and may have had some relation to canal construction, maintenance, and administration.

One of the few mounds to have been excavated is located at Casa Grande in downtown Phoenix. One of the largest mounds in the Salt River Valley, it measures 25 to 30 feet high and 160 by 294 feet across—about the size of a modern football field. Strategically located at the headwaters of the area's canal system, it may have controlled water flowing through the majority of the canals on the north side of the Salt River. Unlike most mounds, which were constructed of coursed adobe, the Casa Grande mound also used locally obtained caliche, sandstone, and granite rocks for support.

The Casa Grande platform mound was partially excavated in the 1930s. One of the structures unearthed atop the mound was an adobe building with two doorways, oriented such that sunlight would stream in one of the doors and out the other at sunrise on the summer solstice. This is one of several lines of evidence suggesting that the Hohokam were accomplished astronomers. Another example is the top floor of the Great House at Casa Grande Ruin, which has a round window that aligns with the summer solstice, as well as other features that align with other solar and lunar events.

The prevalence of platform mounds in Hohokam settlements is yet another factor (along with ballcourts and trade items) that some researchers use to support the theory of a cultural connection between the Hohokam and Mesoamerica. Mesoamerican societies such as the Toltecs, Aztecs and the Maya all built platform mounds. However, Mesoamerican mounds tended to be much larger than those built by the Hohokam. Also, platform mounds were a feature of other North American pre-Columbian cultures, including Poverty Point culture, Troyville culture, Coles Creek culture, Plaquemine culture and Mississippian culture—none of which are thought to have any connection to Mesoamerica.

Why the Hohokam disappeared is a matter of much debate and speculation. What we do know is that the demise of the Hohokam culture coincides with the disappearance of virtually all major cultures in the American Southwest, including the Anasazi, Sinagua, Salado and Mogollon. The prevailing theory is that changes in weather patterns (drought) caused widespread crop failures and led to the breakdown of these complex societies. This is supported by analysis of tree ring data, which shows periods of drought interspersed with periods of above average rainfall. In the specific case of the Hohkam, there is speculation that consecutive years of drought was punctuated by periodic flooding which damaged or destroyed the canal system on which they depended. Others have suggested that the canals silted up, or that their fields became too mineralized after centuries of irrigation and evaporation to support crop growth.

Some researchers propose that cultural strife caused by changing religious beliefs or overpopulation led to the collapse. Still others note that the fall coincides roughly with the arrival of other Native American cultures from the north (the Apache and Navajo), who's migration may also have been climate related. Evidence of burned pueblos, unburied bodies, and in some regions a retreat to more defensible locations lends support to the theory that regional strife played a role. Many of these theories are not mutually exclusive. How the pieces fit together is a subject of ongoing research, the results of which will be fascinating to see.